This week, a famed Fort Worth pizzeria celebrated 50 years of greatness in serving up its rendition of the Italian pie.

Long ago, Mama’s Pizza put a steel skyscraper-sized stake in the marketplace with a business built on a superior product and service, both of which remain to this day splendid in every way.

Most everybody who has spent any time in this part of North Texas has a memory of the place.

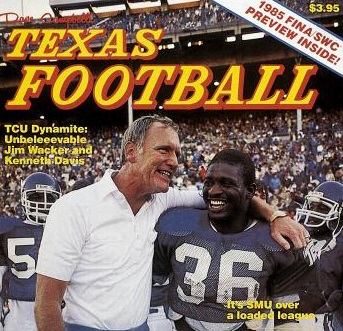

One of them involves one of the most infamous episodes in the history of TCU and the then-owner of Mama’s, who was alleged to have had a role in the paying of seven Horned Frogs football players in the early 1980s.

Chris Farkas, a 1971 TCU graduate, always denied he was part of any slush fund that involved, among others, Heisman Trophy candidate running back Kenneth Davis, who confessed to the whole scheme after one of coach Jim Wacker’s sermons on the perils of players accepting gifts from school boosters.

But some of Farkas’ personal papers, recently obtained by Sptspage, might shed clues as to Farkas’ role, and possibly the mechanics of a payment system that resulted in Davis and eventually six others being kicked off the team in 1985 and landed the TCU football program in hot NCAA water.

The documents were discovered by a close friend in Farkas’ home at the time of his death at age 54 in 2003. They have never disclosed until today.

One document is titled the “$700 per week busboy.” It reads:

“A favorite method of subsidy was used by a California school when a prominent restaurateur provided football players with summer jobs in his restaurant. Each day, some customer – alumni – would leave a $100 tip which the player-busboy became the recipient.

“Other benefits included free meals and a schedule that permitted working out, running, and weight training.

“Other common transfers of cash included summer jobs on oil rigs (at $23 per hour). Often the player never saw the rig let alone worked on it!”

There is no context to any of the documents. They are handwritten on notebook paper and composed as if for a book, maybe, or perhaps even a proposal. It isn’t known.

The papers also don’t shed any light on Farkas’ guilt or innocence, though players at the time said they received money from him. Farkas never indicates whether this was done at TCU.

The schemes outlined in the papers also don’t fit into the machinery of the slush fund that prominent alumni booster Dick Lowe admitted he led.

Lowe acknowledged in a letter of resignation from the school’s board of trustees that he met with head coach F.A. Day and some assistants at another Fort Worth restaurant, the Carriage House, to hammer out a payment system for recruits some time in 1980.

Everyone was on board, he said, including the head coach, who was fired in 1982 after 12 victories in six seasons.

Lowe had personally recruited Davis, flying to Temple — along with Farkas, it has long been alleged — to persuade Kenneth to switch his commitment from Nebraska to TCU.

In his letter, Lowe added that he had grown tired of the scheme before Dry was fired. Lowe, a TCU football letterman during the Dutch Meyer years, called his role a “stupid mistake born out of almost total frustration.”

“At the time … it seemed as though almost all our people had given up,” he said. “Some board members were saying we could no longer compete and were wondering ‘out loud’ if we shouldn’t discontinue the football program. I felt we could compete and also felt the football program was a rich part of TCU tradition.”

When Dry was fired, an assistant came to Lowe with a list of players receiving monthly payments. The list of players was lengthier than Lowe, an oil executive, said he had realized, and he said he couldn’t support such a list.

The assistant said he would talk the players and feel out what they would do if the payments stopped. There was fear among both that if the payments stopped, the players would either transfer or go to the NCAA with what they knew.

The assistant came back with a list of nine, who said they expected to continue to receive the payments or turn in TCU to the NCAA.

“The alumni (including me) are a bunch of fools,” Lowe wrote in his letter to chancellor William Tucker. “They are trying to help their schools. Coaches don’t really appreciate it, and the players use them.”

Lowe did not say, other than himself, who was involved in supplying the financial resources or which players received gifts. But a Star-Telegram story at the time quoted Lowe as saying that as many as 50-60 boosters had paid 29 of Dry’s players.

The plan, he said to a reporter then, was to get through the 1985 season, clear the books with the players affected when they finished their eligibility, and start again clean.

“We almost made it,” Lowe said. “If we could have held on for three or four months … then we could have been clear of all this, and we’d have a clean program.”

Instead, during the week that the Frogs were scheduled to play at Kansas State, Davis went to running backs coach, Ron Perry, and tearfully spilled the beans. Perry immediately went to Wacker, who promptly informed the NCAA.

Farkas, at the time, said he had never given any money to Lowe “or any other TCU alum for any slush fund. I knew there was the possibility it could have existed, but I did not contribute to it.”

On the other hand, Farkas said he did employ a number of TCU players – in fact, five of the seven suspended — but said all the payments they received were legal.

“If the kid works for you, you’ve got to pay him,” he said at the time.

Were they busboys earning “$700 per week?” No one has ever said.

Farkas also said he was, indeed, quite active in recruiting for TCU. At the time, boosters were allowed to make contact with recruits before an NCAA regulation halted that in 1983.

“Within the limits established I met with many, many recruits, but I have not recruited for TCU since Coach Wacker came here,” he said.

Wacker, Farkas said, had confronted him about “a rumor he heard” on three occasions. Wacker claimed that he had been tipped off 10 months before the scandal broke by a former employee at Mama’s Pizza. Farkas defused the rumor by explaining to Wacker that the employee was dishonest and had an ax to grind after being fired for stealing cash from the register.

“At one time, Coach Wacker called me in and asked me if I had bought three kids new cars. I certainly had not done that,” Farkas said.

“A favorite method of attracting an athlete, whose decision will reflect the choice of the parents is to offer the parent a job,” Farkas wrote in a section titled “Hiring Mom or Dad.”

“When the father of a family of six is earning $800 per month, it is simple to find an alum to hire the man for twice that amount or even 10 times that amount.”

Throw in a house full of furniture, repair a roof, and buy mom a new washing machine and “you have just signed another blue chip,” Farkas wrote.

The best time to offer a job is during the player’s high school career.

The father of Egypt Allen, one of the dismissed players, said in 1985 that he’s sure if the players had been offered something they would have accepted it. “I wish an alumnus would offer me something.”

A third section of the Farkas papers involved the “incentive bonus program.”

“Contact with players the week before the game provides the opportunity to give each favorite player an added incentive to excel in the upcoming Saturday game.”

Farkas provided examples:

- $100 to an offensive back or receiver for each touchdown scored

- $100 for each 100-yard game (rushing or receiving)

- $100 for each fumble recovery

- $50 for each pass interception

- $50 for each opposing player who is put out of the game by a hard hit

- $50 for each time the player is a starter on game day

- $50 for each “specialty team” player who makes a solo tackle on a punt or kickoff

- $1 for each yard a punt or kickoff is returned

The scandal hit the news on the night before the Horned Frogs were scheduled to fly by charter to Manhattan, Kan. Longtime Star-Telegram columnist Gil LeBreton, now the editor of Sptspage, was on the team plane.

“It was like a flying hearse,” LeBreton recalled. “Guys were crying. Coaches were crying. Most of the players hadn’t been to sleep. They had either cried all night, or they were probably worried about whether their names would come out.

“It was an unforgettable weekend. Wacker looked like he had just buried his mother.”

Somehow, TCU won the next day 24-22. The headline in the Star-Telegram read, Frogs Win Anyway.

But TCU would only win once more that season. The dismissals of Davis, Allen, Gary Spann, Gearld Taylor, Darron Turner and Marvin Foster — Ron Zell Brewer came forward and confessed the following week — sent the Frogs reeling after a groundbreaking 1984 season. TCU finished 3-8, 0-8 in the Southwest Conference, a year after going 8-4 and playing in the Astro-Bluebonnet Bowl.

Wacker and TCU officials believed that a prompt confession and full cooperation would spare the NCAA rod. Indeed, David Berst, NCAA director of enforcement, said at the time, “This is an instance where the institution took the bull by the horns. If you want to avoid penalties that could be more harsh, then there is a message here.”

TCU went as far as to dispatch drivers to shuttle NCAA investigators to and from the airport.

But when the penalties were announced the following spring, the NCAA showed no mercy. TCU received a one-year bowl ban and was limited to 10 football scholarships in 1987 and 15 in 1988. The school had to return television revenues from 1983 and ’84.

The loss of scholarships savaged the program.

“It wasn’t the death penalty but it was pretty damn close,” Windegger said. “It hurt us for 10 years.”

As part of the sanctions handed down by the NCAA, six boosters were banned from athletics activities.

Lowe was one. Farkas was believed to have been another.

An assistant on Moe Iba’s basketball staff, which replaced Jim Killingsworth’s in 1988, recalled clearly a directive handed down on the first day by athletics director Frank Windegger: “If you’re seen in Farkas’ company, you’re fired.”

That seemed to be quite a heavy price to pay for misguided love and loyalty to your alma mater.

And for the coaches in the athletics department, that meant no Mama’s Pizza.

That was just downright unfair.