Editor’s note: Donald Curry is being inducted in the International Boxing Hall of Fame in ceremonies this weekend in Canastota, N.Y. PressBox DFW wrote about the honor and Curry’s distinguished career in February.

In Fort Worth, it’s only a slight overstatement to say that Donald Curry is as legendary as the Stockyards, the Acre, the Hawk, or even the camp Ripley Arnold’s men staked into the ground at the banks of the Trinity in June 1849.

Yet, until recently the only monument to his world championship boxing career was a Wikipedia page.

He was, the analysts gushed at the time, the best fighter in the world, pound-for-pound, after succeeding Sugar Ray Leonard as the unified welterweight champion of the world.

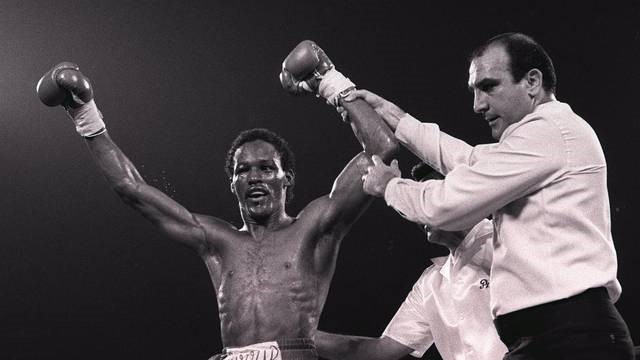

“Donald Curry is on the precipice of greatness,” referee Mills Lane said on Dec. 6, 1985, the night the “Lone Star Cobra” conquered Milton McCrory with a stunning left hand in a second-round rout in Las Vegas. “When history tells the story of him, he may go down as one of the greatest.”

He was, many others asserted, “the next Sugar Ray Leonard.”

History’s story is a far different one than prophesied, not because of a misjudgment of his ability but because of the tragedy that stems from greed, which decimates like a cancer.

In the social media parlance of our day, it’s complicated, but, nonetheless, Curry’s undeniable greatness was finally acknowledged in December.

The big wheels of the International Boxing Hall of Fame called to tell him he would be joining the greats among his sport in the modern era, including Ali, Arguello, Camacho, Cesar Chavez, Duran, Foreman, Frazier, Hagler, Hearns, Holmes, LaMatta, Leonard, Liston, Louis, Marciano, Norton, Patterson, Spinks and Tyson.

None of them need first names, and in boxing circles, neither does Curry, who will be formally inducted in June in Canastota, N.Y.

“This is the greatest moment of my life,” Curry, 57, said in a phone conversation on Monday. “Any athlete of any sport would love to achieve the highest honor in their sport.

“That means you’re a bad dude.”

The IBHOF is a relatively new venture. The ribbon cutting on the museum took place in 1989, and the first class, which included Ali, was shown to their places the next year.

Curry’s inclusion is a tribute to his triumphs and his unmistakable contributions to the sport.

“It’s past overdue. He should have been there a long time ago,” said Paul Reyes, who began training Curry as a 7-year-old. “Donald made history here in Fort Worth. Not only was he the first world champion from Fort Worth, I believe he is the first in the [boxing] hall of fame.”

Fort Worth’s boxing history is a good one.

Nick Wells knocked out Larry Holmes at the 1972 Olympic Trials at TCU’s Schollmaier Arena, then Daniel-Meyer Coliseum. In addition to Curry, the world champions have included Stevie Cruz, Gene Hatcher and Paulie Ayala. Sergio Reyes was a member of the 1992 U.S. Olympic team.

Curry’s step-brother, Bruce Curry, lost to Leonard in the finals of the 1976 Olympic Trials and later won a world championship.

Curry was indeed a “bad dude” and the baddest of all of them to come out of Fort Worth. In Bob Arum’s opinion, he was the “crown prince of boxing.”

A five-time national champion as an amateur and a widely recognized record of 400-4. (Curry believes he had more than 404 fights but is certain he lost only four times.) A 1980 Olympian and gold-medal favorite, but who didn’t get his chance at a Wheaties box because of international dispute with the Soviets.

The U.S. boycott denied Curry the possibility of the Olympic gold medal platform so many have used as a financial nest egg through commercial opportunities, not to mention a jump-start to his professional career.

In addition to the welterweight titles, Curry later won the WBC junior middleweight belt.

In 1985, Curry was selected Fighter of the Year by The Ring, boxing’s bible, an honor he shared with Marvin Hagler.

Curry did it all with an incredible quickness and by being economical with his energy.

The peak occurred where it all started as an amateur, Will Rogers Coliseum, for a welterweight title defense against Eduardo Rodriguez in the spring of 1986.

He admitted at the time that he was nervous as more than 8,800 fans awaited his entrance. It was the largest crowd to ever see a boxing match in Fort Worth.

Mayor Bob Bolen was there, as was Jim Wright, then the U.S. House Majority Leader, and Texas House Speaker Gib Lewis.

Dallas Cowboys receiver Mike Renfro, a native Fort Worthian, was there, as was Al Oliver, the former Rangers outfielder. So was Chuck Curtis, recently out of a job as the last UT Arlington football coach.

Bruce Curry also sat nearby.

As Curry marched toward the ring and the cheering hometown, in front of him were his other brother, Graylin, and friend Alfred Jackson carrying his IBF, WBA and WBC belts into the ring.

Coming home to defend his titles was his most special triumph. (He won the WBA belt, his first, at the Fort Worth Convention Center, then owned by Tarrant County and called the Tarrant County Convention Center.)

Curry vanquished Rodriguez with a left hook followed by a sweeping right that knocked “Chita Ruiz” to the blue canvas at the 2:38 mark. Rodriguez insisted it was a leg cramp that caused him to lose his balance. Curry was certain that it was the left hook.

That Rodriguez took a two-minute nap after the left hook landed seemed to validate Curry’s side of the story.

Enter the underbelly of the business of boxing.

Speculation about a fight with Leonard, who had opened the door in the welterweight division with his premature retirement because of an eye injury, ran rampant. Also on the radar was a planned move up and a bout with Hagler.

At the time, Curry and Hagler were the only two undisputed champions in boxing.

Curry announced that he was planning a move to the middleweight division. As a preliminary move, he had a fight with junior middleweight champion Mike McCallum and a guaranteed $1 million contract.

In a lawsuit later filed by Curry’s camp, Leonard and his attorney Mike Trainer met with Curry and became advisers. According to Curry, the two tried to talk Curry out of the McCallum fight in addition to a move up to the middleweight class, thus conspiring to keep Curry from Hagler.

Curry indeed ultimately decided to back out of the fight and remain at welterweight.

A few weeks later, the Leonard camp announced a return to the ring with a bout with Hagler.

“I want to get Ray in the ring, put him on my lap and give him a spanking,” said Curry at the time.

No one could have known that instead of fortune, Curry’s career was heading 100 mph toward misfortune.

Like that brilliant left hook, it was all over in a flash. It was only months later, in fact, September to be precise, in an ill-fated meeting in Atlantic City with Lloyd Honeyghan, an 8-to-1 underdog to the 25-0 Curry.

From the start, it appeared Curry wasn’t ready for the fight. By the sixth round, with a bad cut about his left eye – caused by a headbutt — Curry was done, a TKO the final result, and his nine-month reign as welterweight’s king over.

Honeyghan’s victory is still considered one of boxing’s biggest upsets.

Curry was never the same.

As it turned out, the personal and business relationship that mattered most to him was broken, and that was his undoing.

Reyes, mere weeks from his 80th birthday, remembers like it was yesterday getting involved with pee-wee boxers. In his first class were nine 7-year-olds. Curry was one of them.

“Little did I know I had a world champion on my hands,” Reyes said.

Before turning professional after the Olympic debacle, Curry chose David Gorman as his manager and decided to keep Reyes as his trainer, a decision that surprised the trainer. After all, everybody, from coast to coast, wanted to be Curry’s trainer.

He trained out of Gorman’s gym on South Main Street.

However, prior to the fight with Honeyghan, Curry’s management team was coming apart, and the break in the relationship doomed him.

More of the vultures of boxing descended on Fort Worth.

Akbar Muhammad, an executive in Arum’s Top Rank organization, had moved in on Curry as early as 1982. By the time of the Honeyghan bout Gorman was essentially out.

“I told Gorman, when [Muhammad] first came to the gym, ‘Gorman, you better watch that man,’” Reyes said. “He didn’t believe me. Gorman didn’t listen.”

Whatever Muhammad’s motives, his decisions hurt Curry’s career, beginning with the Honeyghan fight. He took over every facet of the fighter’s career, even micromanaging his routine and diet, which led to Curry being out of shape and heavy against Honeyghan.

“That’s why he lost his title,” Reyes said. “That guy messed him up. Don was heavy. Anybody would’ve beaten Don that night. He was too weak.

“I had him on a good diet, and Akbar changed all that. Like I told Don, I don’t believe in changing anything. Might want to add something, but when you’re winning you don’t change.”

The decision to change managers was ultimately Curry’s.

It was the worst of his career.

His best advice was coming from Gorman and Reyes, both of whom had his best interests at heart.

“Mr. Gorman knew me better than anybody in boxing except Paul,” said Curry, who drove to Reyes’ gym to personally tell his former trainer the news of his hall of fame selection.

Gorman died at age 61 in 2004.

Gorman “would have been just as happy as I am” about Curry’s induction, Reyes said.

There are many who dispute Curry’s selection, citing his fleeting prime.

They can have their opinions about the importance of shelf life. Curry’s moment was as impactful as any others of his era. He successfully defended any one of three of the welterweight titles nine times.

His boxing ruin wasn’t in ability or shelf life, but in what Chinese philosopher Lao-tzu put his finger on more than 2,000 years ago:

There is no greater disaster than greed.