The spectacle that was the IBF welterweight prize fight between Errol Spence Jr. and Mikey Garcia in Arlington on Saturday stirred the imagination.

Extravaganza can do that, and at AT&T Stadium it’s always a display that far surpasses something even, say, Billy Rose or Barnum could have ever dreamed.

That’s the way the chief promoter and boss does it there.

In another time but in the same proximity another promoter wanted to do something much the same in North Texas.

Unfortunately, that was a time when such a thing was as prohibited as liquor at the First Baptist Church of anywhere.

It was 1895, and engaging the fob in Dr. Emmett Brown’s DeLorean time machine … .

Jerry Jones meet Gov. Charles Culberson, the only governor from Dallas and later buried on Fort Worth’s North Side.

The promoter in those days was Dan Stuart, persuasive and opulent, who had up his sleeve a championship heavyweight bout between “Gentleman Jim” Corbett and “Ruby Robert” Fitzsimmons in Dallas’ grand new amphitheater covering four acres a quarter-mile northeast of the state fairgrounds, which had been advertised as the coming of the second-largest building, in terms as seating capacity, in the world.

Dan Stuart

City leaders envisioned the stadium as a permanent structure – they were saying that in those days, too – for athletics and conventions.

In fact, at the state fair that October, the same month as the fight, noted orator William Jennings Bryan, who next year would begin the first of three runs for the U.S. presidency. But this would be bigger, they all predicted, each and every one of the arena’s 52,000 seats occupied in Dallas, then a city of about 45,000.

Boxing had been outlawed in many states, but not Texas, not completely anyway. So, city and state officials smelled a big money and public relations opportunity.

Stuart, by force of personality and a checkbook outbid all the others by offering a purse of $41,000, of with $39,000 would go to the winner.

That was serious scratch in those days – more than $1 million in today’s money — when things were happening in America the Beautiful, the first time, in fact, anybody had heard of the poem that would become a memorable jingle. In August of that year, Old West outlaw John Wesley Hardin finally got his, meeting his demise at the end of a bullet fired by an off-duty policeman in a saloon in El Paso.

El Paso would become part of this story, too.

Anyway, the fight between the two premier pugilists of the day in Dallas was a very big deal.

A few years earlier, Gentleman Jim was the first to win a heavyweight championship bout under the code of the Queensberry rules with boxing gloves. Before then, they did the way John Wayne would’ve done it with bare-knuckles.

This “glove contest,” as it came to be called among all those with opinions about it – and there were plenty – would be the “most scientific boxing contest in the world” and the “premier event in the domain of sport,” the mayor assured his subjects.

The Dallas business community was onboard, too. Though slick marketers had yet to come up with “economic impact,” they insisted that the bout and all those who would come far and wide would result in a residual benefit for all the business owners.

Ruby Robert

Gentleman Jim

Even in Fort Worth, there were supporters.

Alderman M.A. Spoonts believed the culture could use a kick in the shorts. He was particularly concerned about men losing their vigor.

Boxing promoted all the necessary habits to curb this downturn.

“While the dudes and young men are sitting around idling away their time and ruining their health by smoking cigarettes, the young ladies are adding strength and beauty by daily bicycle spins, dumbbell practice, and in many other ways.”

What feminist today couldn’t have appreciated his anti-smoking message? Still, it is presumed that any “Women for Spoonts” grassroots campaigns that existed in those days was organized not for the city council, but rather for “Spoonts for Swine Breeders Association.”

Ahead of his time was M.A. Spoonts.

All was charging ahead smoothly until a stiff wall of opposition emerged.

The evangelicals came out swinging.

Rather than a benefit to the welfare of community, as the Alderman Spoonts advocated, boxing was an “abomination not to be tolerated by any civilized community.”

Organized fighting was not up to the standards of the laws of either God or man.

They also had in their corner a very powerful ally.

This fight between Gentleman Jim and Ruby Robert would happen only over Gov. Culberson’s dead body, and that was not an option.

He vowed he would prevent it.

Culberson today is little known, but he had key roles in history. Culberson County in West Texas is named for his father, David Culberson, a lawyer and Confederate soldier. The last part should in no way taint the son. Charley Culberson spent is career opposing the KKK in every way.

Elected governor twice, in 1894 and 1896, Culberson ran and was elected elected by the Texas Legislature in 1899 to the U.S. Senate, where he would stay until defeat by popular vote in 1922. Many account his loss to his opposition to the KKK. He died in 1925 after being in declining health for several years. Culberson won reelection in 1916 without ever having visited the state, citing health problems. His problems, historians attest, had as much, maybe everything, to do with alcoholism than anything else.

Upon his death, he was brought back to Texas and buried in a plot owned by his wife’s family, the Harrisons, in Oakwood Cemetery in Fort Worth. A historical marker adorns his grave site.

Toward the end of his prime, he was a crucial figure in the election of Woodrow Wilson, inviting and introducing the then-governor of New Jersey to the Texas state fair in 1911 for an address as a presidential campaign warmup. He vigorously supported Wilson the next year and as a delegate was credited with swinging the state to him in the 1912 Baltimore convention.

Behind the scenes pulling the strings was his Karl Rove, who turned out to be more more powerful than he was. Edward “Colonel” House helped engineer Culberson’s political career and did the same for Wilson’s first presidential campaign.

Charles Culberson

House would go on to become, even to this day, one of the most powerful presidential advisers in U.S. history.

Meanwhile in the Senate, Culberson made a mark, crafting what became known as labor’s magna carta in the Clayton Anti-Trust Bill, declaring that labor was not a commodity to be bargained and sold and upheld the right of collective bargaining. He also carried Wilson’s WWI legislation through the Senate.

Unfortunately for Dallas and Stuart, Culberson was a roadblock in 1895, and his position was immovable.

“Men of Texas,” Culberson declared, “have you thought well of what you are going to do? Do you intend to allow a prize fight to be held in your state? Are you content to let these men from California and New York say that the law will not let them fight at home, but that they can come down to the rowdy state of Texas and pull off a ring battle?”

Reminded by a bystander that there is no law completely outlawing the sport, Culberson said: “No, there is no law, but there will be.”

Unhelpful to boxing’s cause was its association with gamblers and swindlers, the same types who would infect baseball in the 19-teens. Despite what our Fort Worth alderman believed, the sport was not a healthy exercise, but corrupting and degrading, the governor believed.

Several days later, the governor acted, calling the Legislature into special session on Oct. 1 – 30 days before the scheduled bout — with the express purpose of banning boxing in Texas, once and for all, this “affront to the moral sense and enlightened progress of Texas … to denounce prize fights in clear and unambiguous terms.”

It didn’t matter that the fight enjoyed the overwhelming support of Texans. The politicians, though surprised by the governor’s called special session, thought they knew better for one reason or another – it’s politics after all. Two days later, on Oct. 3, boxing, “and all its kindred spirits,” was legislated out of Texas.

The bout was off. Plans for the stadium in Dallas scrapped. William Jennings Bryan was back on as the state fair’s featured event. (Oh, boy.)

The bill met all of Culberson’s demands. He signed it.

The three days represented the most “outstanding act” of his three decades in politics, it was written at his death, “believing its effect upon his state would not uplifting or salutary,” U.S. Rep. Thomas Blanton of Texas said in 1925.

Arkansas’ governor put his foot down, too. Any attempt to stage the fight there would be met with his executive duties. Gov. James Paul Clarke said would enforce Arkansas’ anti-boxing laws even if it meant enlarging “the walls of the state penitentiary, if needs be, to accommodate the crowd.”

The U.S. Congress passed a law forbidding the bout to take place in Indian Territory.

Gentleman Jim, tired of the prolonged uncertainty, simply retired. He was replaced on the card by Peter Maher, the Irish brawler, who would face Fitzsimmons, a blacksmith from the UK.

Peter Maher

A bout between Corbett and Fitzsimmons would finally be conducted in March 1897.

The announcement of that bout was announced in Taylor’s Hotel in January 1897 in Jersey City. The news account noted that “Dan Stuart of Dallas, Texas, who made the match and claims to be able to pull it off, was present.”

Stuart did get that one done, in Nevada, after the state repealed its anti-boxing laws. Fitzsimmons shocked Corbett, winning by TKO in the 14th round.

This time, still looking for a site, El Paso entered the picture.

They couldn’t do it there – the Texas Rangers made sure of that — but Juarez was just across the river.

But there, organizers and city leaders were met with an unambiguous message: No hay boxeo aqui.

Stuart was getting worried. Though the purse had dwindled, it was still $10,000 and contractually he had to forfeit $5,000 if he couldn’t find a venue.

In the end, this is what happened: Judge Roy Bean, who put the “O” in opportunity, found an opportunity to get in on the action.

He made a deal with Stuart: The fight would be on the other side of Langtry, Texas, home of Judge Bean, “the Law West of the Pecos.”

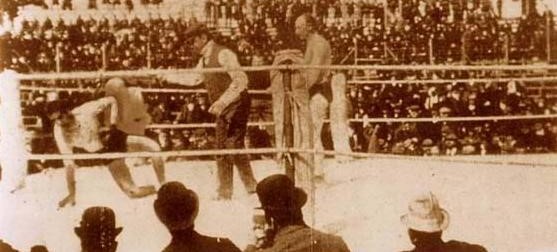

Taking fight fans from a special train more than 365 miles to the southeast of El Paso (215 miles west of San Antonio) to no-man’s land, the fight was staged on a sandbar in the Rio Grande in Mexico’s Coahuila, on a damp day, Feb. 21, 1896.

The combatants were on the train also.

Texas Rangers, who had tailed the train riders from El Paso, could only sit idly by, unable to do anything about what they watched in the river canyon below. Officers of Coahuila, likely compromised, were nowhere to be found.

Stuart finally got his fight – Bean realized an “economic impact” through sales at his bar – and fight fans, who paid $600 in today’s money for tickets to the fight and another $360 for the train ride, got jipped.

Fitzsimmons knocked Maher to the canvas with a right uppercut to the jaw.

The fight was over in 95 seconds.