Nothing struck fear into teenagers – and coaches – quite like a provision in 1984’s Texas House Bill 72, which for all practical purposes was a union of the worst of Hollywood’s bogeymen.

No pass, no play.

If a Texas public high school student-athlete failed a course during any six-week reporting period, he or she was required – by law – to sit out from their sport for six weeks.

In Texas, where football and Jesus Christ share equal billing, this caused a flood of disquiet unseen since the days of Cabeza de Vaca, the Spaniard who stumbled onto present-day Presidio, where it hadn’t rained in two years.

Please, the natives asked whom they considered a god, order the sky to rain.

It was as serious an impinging as there had ever been on the state’s fabled Friday nights.

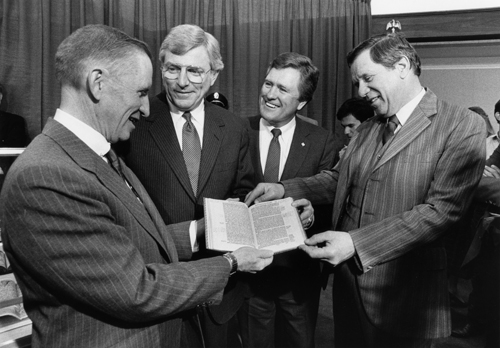

No pass, no play was the brainchild of the Governor’s Select Committee on Education, chaired by Ross Perot, then merely a Dallas multimillionaire, who died this week at age 89. The blue-ribbon panel called together by Gov. Mark White is one of Perot’s lasting legacies.

If there was a time Perot didn’t attain what he wanted in this world, it was never noted. That even includes losing a presidential election. Perot might have asked for a recount had he won the presidency in failed attempts in 1992 and 1996.

He wanted to make points and spent millions to do so.

Perot, the face of the committee and its larger-than-life influencer, was going to get what he wanted, pushing as only he could the committee’s recommendations into law during a special session of the Texas Legislature in June of 1984.

Perot hired Houston attorney Tom Luce to spearhead the legislative effort in Austin, and he loaned out lobbyists from his Electronic Data Systems company to crusade for the bill. He even went so far as to deploy female EDS employees to go to Austin to fraternize with legislators and host parties.

The $2.8 billion education reform package was in many respects ahead of its time. The law established a state preschool for children with disadvantages, such as poor and non-English speakers. It shifted school aid from rich to poor school districts, reduced class sizes in early grades and toughened academic standards.

It also provided raises to teachers but linked those raises to performance and mandated testing for teachers.

It was no pass, no play, however, that caused the most handwringing.

Perot and Gov. White were the faces of that part of the movement, which was met with universal condemnation by high school football coaches.

Lt. Gov. Bill Hobby of Houston penned verse that provided some insight into the special session setting.

What with taxes and all,

Lobbyists were thick as roaches.

So, it took all the Luce women

to win the war against coaches.

No pass, no play grew out of the committee’s findings that schools were sacrificing academics at the altar of extracurricular activities, particularly sports.

More particularly, football.

Everywhere Perot went to discuss the committee’s findings he told the story of a boy who had missed 35 days of school so that he could exhibit his pet chicken at livestock shows.

But he was unsparing in his critique of Texas and its romance with football, American style.

Texas had first-rate education, he charged, in only drill team, band and football.

It was cultural. Texans didn’t care enough about education. Schools spent money on towel warmers and multimillion football stadiums while “kids who can barely read and write were leaving school at noon to cook hamburgers so they could make payments on their cars.”

Of driver’s ed: “That’s where they house the assistant coaches who are too dumb to teach regular classes.”

It went beyond hiding assistants in driver’s ed.

Coaches being promoted into administrative roles in school leadership was another of Perot’s targets. At town halls, he would ask principals in attendance to stand. If you were a coach, he then instructed, sit down.

Most everybody sat down.

Coaches felt humiliated.

“It was like being in a sword fight with a pocketknife,” said an official of the Texas High School Coaches association.

To no surprise, coaches around the state got into a defensive posture. The goal was well intentioned, but the bill would have unintended consequences. It wasn’t just about winning and losing on a football field, they said. Team sports were part – a very important part — of a well-rounded education and taking that away from kids would cause many to simply drop out of school.

Some believed the penalty for failure should be three weeks. Others thought a player should be eligible the moment his grade rose to passing. Still others believed the benchmark should be an average of all classes. There were student-athletes in National Honor Society, they contended, who had all A’s, but failed one class. That made them ineligible.

For two years, coaches lobbied the governor’s office to push for relaxing the rule, but White refused to yield, which many noted was ironic considering the governor vowed in 1982 not to support any bill that raised taxes. He did so in 1984 and proposed another increase in 1986.

Coaches couldn’t punish Perot, who held no political office.

But they could make the governor pay, and they did the first chance they got by hitting him where it hurt the most — the ballot box. That was 1986, the year White would face his political rival, former Gov. Bill Clements in a bid for re-election. White had defeated Clements, then the incumbent, in 1982.

The bulk of football season was right before the election, and coaches intended to use that visibility to impact the hearts and minds of voters. No one has more stature and sway, especially in rural Texas, than a football coach between September and November.

It wasn’t Ross Perot or any governor who was Caesar, but rather football coaches.

“We’ve had to make a stand,” said Charlie Johnston of Childress, then the president of the Texas High School Coaches Association. “No pass, no play has been around a couple of years, but there’s more interest this year because it’s an election year. I think we’ll be a force in the election.”

The annual meeting of the Texas High School Coaches Association in July was more in the spirit of a political convention. All that was missing were smoke-filled back rooms. Actually, those weren’t missing, just simply not on location. Those were at a nearby bar or bars where coaches mingled, rubbed shoulders and shot the bull.

That was typical of every convention, but that year there was much to discuss and cuss over beer and more beer.

T-shirts spotted in Houston that year included “Mark White: Danger – Keep Away from Children.” Another said, “Will Rogers never met Mark White.”

For the first time — probably the only time — coaches endorsed a candidate for governor.

Mark White did not win that straw poll of the motivated constituency.

They even hosted Clements, who arrived one afternoon to address the convention. The bill, Clements said, needed “fine-tuning.” He was a proponent of relaxing the penalty phase to three weeks.

Anti-Mark White became inspiration, even life itself.

Denison athletic director Marty Criswell said he would mobilize the 30 coaches under him to campaign against White.

“I’m putting them to work to influence the voters we come in contact with: friends, neighbors, the parents of our kids. I hit every civic group before the season starts – Lions, Rotary, Kiwanis Jaycees – and I’m going to try to make this a priority.

“I think Gov. Clements has a greater appreciation for the benefit of extracurricular activities and that you can have a quality education program and quality extracurricular activities at the same time.”

That November, Clements soundly defeated White, sending the governor into public retirement and back to private life in Houston.

Afterward, analysts studied the data. White lagged significantly behind his 1982 showing in the state’s rural areas, where historically support for Democrats was found. That was the same region where educators and coaches had the most influence. (That part of Texas has been solidly Republican since, suggesting more was likely at play than simply opposition to no pass, no play.)

It took several more years, but no pass, no play was finally modified and made less restrictive.

Today, the penalty for failing one or more courses is three weeks, if the student has brought the grades up to passing. Student-athletes are also allowed to practice with their teams during the three-week period.

White never did relent on his belief in the bill as passed originally. That tussle that ensued in 1986, however, between high school football coaches and the governor was as Texas as the Alamo.

And the coaches won, making for bountiful blessings that Thanksgiving.

“We whipped his tail,” Tim Edwards, then Hurst L.D. Bell’s football coach, said at the time of White. “He humiliated us, he pointed fingers at us, but we beat him good.”