Carrollton’s Savannah Broadus returned home a Wimbledon juniors champion, one-half of the unseeded doubles duo that raised a racket at the All England Tennis Club.

In the finals, she and Abigail Forbes, the tennis wunderkind from North Carolina, who will soon be enrolling at UCLA, defeated a team made up of two eastern Europeans, a Latvian and Russian.

Since returning, Broadus has made the rounds with local media, which had taken interest in her triumph and experience in the UK.

It brought to mind that time many years ago when our area hosted one of Britain’s top young women’s players.

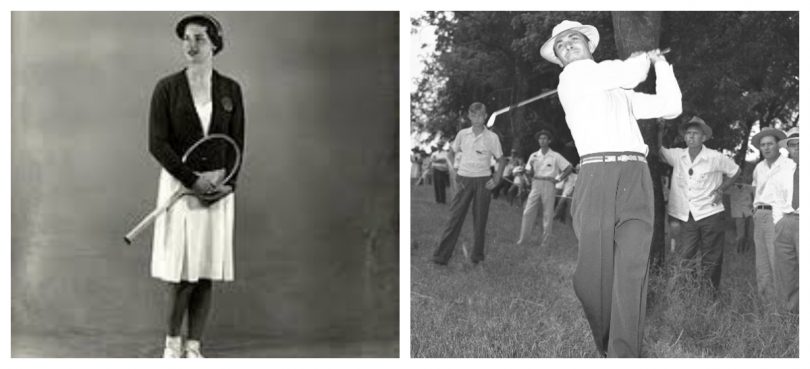

In February of 1941, Mary Hardwick traveled to Fort Worth as part of the touring foursome of Bill Tilden, Don Budge and Alice Marble. Tilden and Budge, and Hardwick and Marble played singles, followed by a mixed-doubles match, all at Will Rogers Memorial Coliseum in Fort Worth.

“I can’t hear myself think,” Hardwick said a few hours before showtime about her radio. “I’ll turn down the wireless.”

She was eager to talk to media about the pressing issues of the day. A portion of the profits from her part of the tour were dedicated to the British war effort. By that time, the Brits were teetering.

Hardwick was in this country to play in the national amateur events in 1939 when war broke out. She stayed here, accommodating the wishes of her parents. She worked for a while in the British War Relief office before she, along with Marble, turned professional.

She had gained repute as her country’s top women’s player after having beaten every Brit she had met since 1937. The year before while touring in America, she defeated every American comer, except Marble and Helen Jacobs.

Mary defeated Helen Wills Moody at Weybridge, England, in 1938, Moody’s first loss since winning Wimbledon in 1927.

She talked about King Gustav of Sweden, a tennis devotee who, Mary asserted, was a better player than Mussolini, who played a little tennis. Mary had hit with the king. She had not played Mussolini, but she had seen him play, leaving with as little regard for his forehand as she had for his fascist government in Italy.

Only the week before, the foursome had played in front of the Duke and Duchess of Windsor in the Bahamas, where the former King Edward VIII and his American divorcee beloved were coping with abdication. She was disappointed the event earned the British War Relief $700 — $12,000 today.

The biggest concern that day was appeasing Tilden, who was well known by then for making known his displeasures. At an exhibition earlier in the state, Tilden curmudgeonly exclaimed: “This court is rougher than a plowed field.”

Hey, fella, we play football here.

Jay Cohn, tennis professional at Colonial Country Club, had been recruited to oversee the construction of the clay court. Work couldn’t begin until two days before. Cohn had examined the soil of the coliseum floor and found clay already there. He will get more from a “diggings” near “Ted Hackney’s Meadowmere courts” to mix a proper blend.

“We hope to have the best indoor court that the pros have played on during the current tour,” Cohn declared.

Ordinarily, at the time, it takes two weeks to get a clay court in playing shape. Cohn hoped to achieve the same results literally overnight by letting a bunch of his “youthful tennis scholars have a war dance on it.”

“Bill and I drove up from San Antonio Saturday,” said Hardwick, who died in 2001 at age 88. “I never tire of talking with him. And I think he is the most amazing athlete of all time. Think of it. He was an athletic contemporary of Jack Dempsey and Gene Tunney. And he can still give the best of the younger players the very devil.”

That was quite a sports year, 1941, for Fort Worth.

Later that year, in June, Colonial Country Club, hosted the men’s U.S. Open golf championship. Craig Wood won by three strokes over Denny Shute, shooting a 4-over par over four rounds. Ben Hogan finished third.

Amon Carter, that “six-shootin’, gusty, husky go-getter whose rise in the world has run such interesting gamuts as selling the newspaper he now publishes,” was put in charge of promoting it, and everybody, literally everybody, was invited.

This was the guy who, when asked to help with this ambitious goal to bring this holy grail of golf to Fort Worth, responded, “What the tarnation is the U.S. Open?”

Though golf was Greek to him, publicity and energy were his games, and he was a scratch player.

“I have received a copy of the official program of the forty-fifth Open Championship of the United States Golf Association at Colonial Country Club and also the medal commemorating the occasion which was engraved to me personally,” FBI director J. Edgar Hoover wrote Carter. “You may be sure that I deeply appreciate your thoughtfulness in sending these to me.”

Carter’s guest list, found among his papers at the TCU library, included Bob Hope and Bing Crosby, Franklin Roosevelt, who had bigger things to attend to as the world was coming apart at the seams, Henry Stimson, the secretary of defense, and Henry Morganthau.

“We realize the difficulties confronting the country in connection with national defense at this time. However, Fort Worth was selected last year and the [Fort Worth Golf Association] committee [tasked with putting on the event] feels they should proceed with business as usual,” Carter wrote to the president. “Therefore, on behalf of the Association, I take pleasure in extending to you a cordial invitation.

“Naturally, I realize this this may be asking a good deal. However, we do want you to know that we will be tickled to death to have you with us as we expect to put the big pot in the little one and see that all of our visitors not only have the opportunity to attend an interesting tournaments, see the best golfers in the country play, but in addition are provided with the usual Texas hospitality.”

He closed with a nudge, reminding the president, who had heard it a hundred times before, that Fort Worth was “Where the West Begins.”

The tournament, Carter declared, would be done “bigger and better than it’s ever been done.”

That hospitality featured a barbecue for 500 golfers and guests at Carter’s Shady Oak ranch. It set the record for bigness, one wrote, “by having 16 men in the quartet,” which entertained during dinner.

When it rained during one round, Carter fingered his notorious bogeyman as the culprit, blaming Dallas.

As expected, the president was indeed a no-show. His son Elliott, then a Fort Worth resident, was likely there.

Bobby Jones, the southern gentleman golfer from Georgia, was there, too. So was Grantland Rice.

“Everything seems much too quiet at home after our experience with your wonderful Texas hospitality. It is quite a strain to find myself back where I have to look after my own entertainment.”

The tournament, the first U.S. Open in the south, went off without a hitch, Jones said.

“Now that you know how to run a golf tournament, I think you should try playing the game.”

Signed, “Bob Jones.”