In the end, for Mike Stone, it was all about love. Maybe it always was.

The former Texas Rangers president wrote his own love story over the last year and half, spending virtually every moment with the love of his life, doing exactly what he wanted to do, in the place he most wanted to be.

He wrote the play, directed it, starred in it and pulled off his own Hitchcockian climax. He even exited stage left with a “gotcha” wink at the despicable disease that took his life.

If only we could all be so lucky.

Stone, 80, died Friday at his home in Ajijica, Mexico, where the sun almost always shines and the breezes off the lake are instantly refreshing. He was exactly where he wanted to be.

Two years ago, after knee replacement surgery in Texas, Stone was having trouble getting his oxygen levels to where they need to be. He was sent home with an oxygen tank and an appointment a month later with a Fort Worth pulmonologist.

Mike and wife Ellen Ray were not prepared for what they would hear. The diagnosis was Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis, a nasty disease that gradually fills the lungs with fibers until suffocation is inevitable. A previous heart attack and his age made Mike an unlikely transplant candidate. Doctors couldn’t or wouldn’t guess at how long he might have left.

There were medicines that might slow the progression of the disease, but Mike didn’t like the severe side effects or the price: $10,000 a month. He vowed he would not leave his family destitute.

Stone, who had just retired after a seven-year professorship in sports management at SMU, and Ray already had plans to move to Ajijica with friends. The diagnosis didn’t stop them. In fact, it made that decision even more imperative.

Away from distractions back in Texas, and with each moment becoming more precious, they could concentrate only on each other.

“I think we wanted one last adventure,” Ray said from Ajijica Tuesday night. “Mike loved it here. The weather is great. We love the people, the culture, the economy.”

Most of all, they loved each other.

They took walks along the lakeside, until it began to be too difficult for Mike to breathe. They did taste tours of the smorgasbord of restaurants in the area and sipped wine at sidewalk cafes. They held hands and watched sunsets together.

They laughed as they shared favorite memories.

“The best part was that for the last year and a half, we’ve spent every single day together,” Ray said. “It was like being on vacation the whole time. There was nothing to distract from each other. There was nothing that went unsaid.”

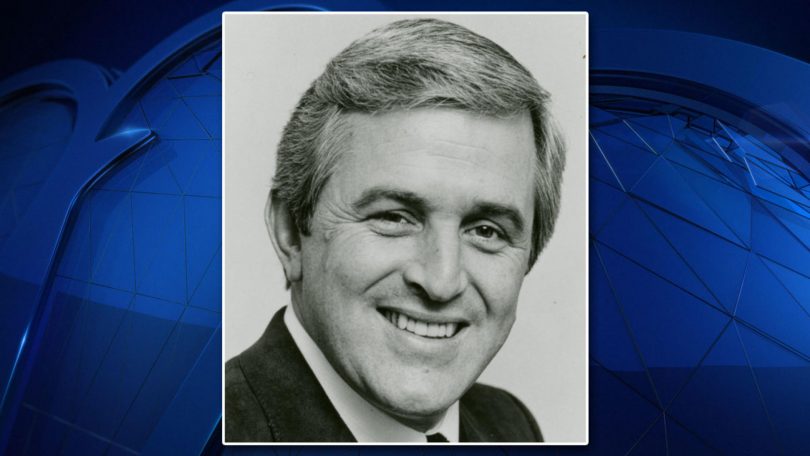

I was a beat writer covering the Rangers for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram when Mike Stone first showed up as a consultant for Eddie Chiles in the off-season of 1982 and again six weeks into the season in 1983.

We did not have a good start. The atmosphere with the media and “I’m Mad” Eddie Chiles was sour. Chiles was losing money, his team was losing games and the press was reminding him constantly of both. Stone stepped right into the middle of a hot mess.

In mid-May of 1983, with the Rangers already in the tank and reeling after a 1-5 road trip to Chicago and Kansas City, Chiles chose an off-day to lock down Arlington Stadium, post armed gates at the gates (in case the media should storm the fortress with pens, tape recorders and the occasional empty Lone Star beer bottle) and bring in his corporate hotshot, Mike Stone, to conduct a business seminar on individual and group goal-setting. You can imagine how well that went over with old-school baseball men like manager Don Zimmer and players like Mickey Rivers, Buddy Bell and Bucky Dent.

“(Stone) talked to us about personal and group goals,” a puzzled Zimmer would confide later, his eyebrows doing jumping-jacks on his cherub face. “Jeez, I mean, I’m supposed to ask these guys every week what they expect to do at the plate. Every one of them tells me they think they’ll hit .500. What am I supposed to say? What do I do with that?”

OK, so it wasn’t a great start, but Stone would learn and much quicker than any of us media critics might have expected. Stone may have started in business, but he fell in love (there’s that word again) with baseball.

Chiles was right about Stone. He was highly intelligent and a quick study. He almost instinctively knew that what might work in a business environment with college graduates was unlikely to get the same results in a baseball clubhouse peopled by those who may barely had passed high school or had just arrived from Latin America.

By the end of the ’83 season, Stone had begun his seven-year run as Rangers president. A year later, early in the ’85 season, he agreed with general manager Tom Grieve that it was time for manager Doug Rader to go. They would bring in young and energetic Bobby Valentine, an early turning point for the franchise. Five years after that, in December of 1988, Stone played a vital role in the signing of a free agent pitcher out of Houston that would re-make the Rangers’ image across the country – Nolan Ryan.

The irony, Zimmer’s befuddlement aside, is that history shows that Chiles was right all along. There is a place for business acumen in baseball when it’s applied within the framework of the game. But it takes men like Mike Stone, who understand that the business they’re in – baseball – is unlike anything they’ve ever dealt with before.

Mike and Ellen didn’t broadcast it when he received his fateful diagnosis two years ago. They’re private that way. His passing Friday came as a shock to the baseball world.

They had just flown back to UT-Southwestern in Dallas to visit the pulmonary clinic there. Doctors told him go where he wanted to go, but to not plan on flying much longer. Mike told Ellen he wanted to go home. Back to Ajijica.

A friend picked them up at the airport in Guadalajara and drove them the 20 minutes to their home. Mike slowly made the walk into the house while Ellen hurried to turn on the oxygen machine there.

Mike collapsed into a chair.

And died.

“It was over just like that,” Ellen said. “We called for an ambulance and they did CPR, but he was gone.

“We figured he had more time. But if he was a planner, he couldn’t have planned it any better himself. The comfort is knowing he isn’t going to suffer the very uncomfortable death associated with IBF.”

Ellen Ray says she will stay in the home by the lake that she shared with Mike over the last year and half, at least for awhile. There are too many good memories there to study, to smile over. She can’t leave just yet. Perhaps she never will.

It was – it is – a 42-year-old love story. They wrote the story together, linking hearts and minds until they could no longer tell where one ended and the other began.

We should all be so lucky.