It’s advisable, particularly with all the readily available social media channels, that in the spirit of promoting the common good, public service announcements – warnings — should accompany the beginning of presidential election campaign seasons.

Think a tornado or civil defense alarms. Seek shelter, the Four S’s have arrived: slander, slurs, snark and self-indulgence plus a drenching of spin for dessert.

Watching these debates – to be crystal clear, any of the two parties’ debates — require a shower and a shot of your preference.

Don’t let anybody tell you that this era is the worst dysfunction in American politics. This is mere typical restlessness compared to other periods in American history.

The only new thing in the world is the history you don’t know, Margaret Truman’s top fan once said.

Another non-new element: race and politics. Race and politics have been a part of the American landscape since the very beginning. Though slavery was very much an issue, the Founders kicked the can down the road on it until the mid-1860s. The domineering issue of the 1900s was Jim Crow and the fight for civil rights, followed by the persistence of equality of opportunity and matters of police propriety.

The day race and politics are no more is the day they’re mowing grass over you and me.

“That’s right, Rocky,” said the man at the highly divisive Republican Convention in 1964 in San Francisco. “Hit ’em where they live.”

A man in the Alabama delegation nearby turned to confront this political adversary, a Rockefeller Republican who had infiltrated this uber-Barry Goldwater gathering. If not for the Alabama man’s wife stepping in, an altercation likely would have resulted on this boisterous evening at the Cow Palace.

“Turn him loose, lady,” Jackie Robinson said, “turn him lose.”

The anecdote was culled from On His Own Terms, a biography of Nelson Rockefeller from the very able Richard Norton Smith, published in 2014.

Jackie Robinson’s legacy as the man who broke baseball’s color barrier, not to mention a pretty good ballplayer, is as secure as the knowledge that the sun will rise and set. It was in August 1945 that Branch Rickey signed Robinson to a contract with the Brooklyn Dodgers. He was assigned to the Montreal Royals.

Robinson led the Dodgers to five National League pennants and in 1955 one World Series title. Jackie was a six-time All-Star and the 1949 NL MVP and later elected to the Hall of Fame.

The most interesting part of him, however, was his political activism in his post-playing days. Robinson was not afraid to mix it up with people in power, to use his voice, as he told John F. Kennedy – not yet a candidate for president – to speak out against racial injustice in politics, labor and employment, education and any of “their related fields.”

“As I have often expressed to you, I think you carry a great responsibility for your people,” Branch Rickey wrote to Robinson, who a month earlier in 1950 had sent a letter expressing sadness in hearing Rickey was leaving for Pittsburgh. “And I am sure that you sense the duties resting upon you because of that responsibility, and I cannot close this letter without once more admonishing you to prepare yourself to do a widely useful work.”

Robinson’s widely useful work naturally was the advancement of the fundamental rights of man for black Americans.

Though a Republican voter for much of his life, Robinson was a man of no party affiliation. Marrying a party was bad politics for black America, he believed. Rather than become content with the support of black Americans, parties and politicians needed to constantly work for the support of the African American constituency and play the two parties against one another.

He wrote to Rockefeller in 1965: “The sooner there is a strong two-party system in New York as well as nationwide, the sooner we get our rights.”

That perspective proved prophetic. In 1961, Sen. Barry Goldwater told an audience of Republican leaders in Atlanta, “We’re not going to get the Negro vote as a block in 1964 and 1968, so we ought to go hunting where the ducks are.” That attitude has persisted.

Goldwater was no racist. In the 1940s the senator desegregated his family’s department store, as well as the Arizona National Guard. What he didn’t like was federal overreach at the expense of local sovereignty.

Robinson held a personal conviction, as outlined in a letter included in a compilation of his missives, First Class Citizen (2007), “that freedom is a thing for which man is innately ‘ready’ by virtue of birth.”

If he were president – had his era been 50 years later, he might well have been an office holder, if not perhaps president — “I would take the position that there are times when it is more important to be a President than to be a politician.”

Robinson liked pols from both parties. He liked Democrat Chester Bowles, the governor of Connecticut and Minnesota Sen. Hubert Humphrey. He did not like JFK in 1960, not at all, accusing the candidate of too close an association with the governor of Alabama and his cabinet.

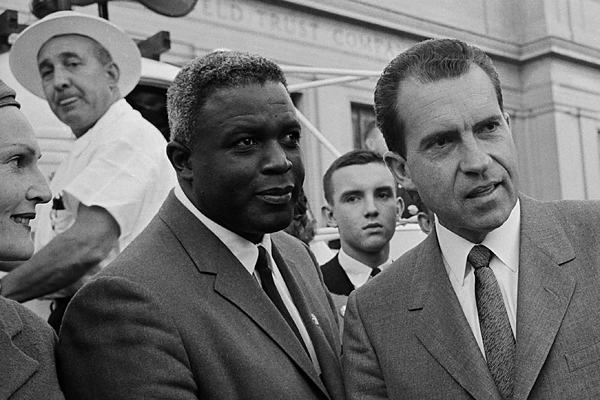

Robinson was a Nixon man, through and through, in 1960, though was dismayed when in 1968 Nixon openly courted the leaders in the South. Still, he reaffirmed his support in 1972, though it was lukewarm at best.

As he neared the end of his life, Robinson wrote a last letter to President Nixon: “I hope you will take another look at where we are going and be the president who leads the nation to accept difficult but necessary action, rather than one who fosters division.”

Nixon this time didn’t reply.

Robinson liked and admired Dwight Eisenhower but soured on him after the hard-fought Civil Rights bill of 1957. Ike, considered a progressive on the issue of race, said there were “no revolutionary cures” to America’s social ills and that it would take “patience and forbearance.” That message was “unwittingly” crushing the spirit of freedom of black America, Jackie said.

“I was sitting in the audience at the Summit Meeting of Negro Leaders yesterday when you said we must have patience,” Robinson wrote to Ike. “On hearing you say this, I felt like standing up and saying, ‘Oh no! Not again.’

“I respectfully remind you, sir, that we have been the most patient of all people. … Seventeen million Negroes cannot do as you suggest and wait for the hearts of men to change.”

Ike replied that as it concerned his comments about patience and forbearance, “I have never urged them as substitutes for constructive action or progress.”

At heart, however, Robinson was a Rockefeller Republican, best described as a philosophy of fiscal prudence and a progressive social conscience.

Rockefeller, the grandson of John D. Rockefeller, had led the effort at the 1960 Republican Convention to include in the platform a civil rights plank that pledged support for seeing Brown’s school desegregation order through, voting rights, desegregation in federally financed housing, and the creation of the Commission on Equal Job Opportunity.

It was Rockefeller who secretly bailed Martin Luther King Jr. out of a Birmingham, Ala., jail in 1963, through a suitcase of cash to MLK’s attorney. Rocky spoke at King’s Ebenezer Baptist Church and gifted $25,000 to King’s Gandhi Society for Human Rights. The sanctuary’s stained-glass windows were restored by “imported Italian craftsmen,” compliments of the governor. Rockefeller paid for King’s funeral, a top aide even picked out a coffin.

When King’s widow needed a plane to finish MLK’s march in Memphis, she had one.

“Of all the men I have met in the political field,” Robinson wrote to Rockefeller, then the governor of New York, “you offer the greatest potential for the things that will make America the country we all want it to be.”

In the end, though, there, too, was disappointment.

Robinson protested when Rocky snubbed a contingent of the Poor People’s Campaign in 1968. Rather than meet MLK’s brother and an activist Catholic priest, Rockefeller dined with a financier and art collector in the name of political expediency as he made his last bid for the presidency.

Rockefeller has to be Rockefeller to win, Robinson said, not try to out-Nixon Nixon.

Rockefeller responded: “Putting on the brakes, retrenching, calling a halt — these are actions alien to my nature. But I have learned from bitter experience that liberalism ceases to work at some point if it is not controlled by realism.

“We have come face to face with the fact that state and local governments are running out of money, abuses have occurred, and an inevitable taxpayer reaction has set in. I am simply trying to bring things back into balance … . All I can say is that I am trying to do my best in a very difficult period, and I hope we can sit down together and talk it over sometime soon. Just let me know if you want to.”