As part of my personal rules for maintaining the public health through good citizenship, at least one eye is kept on the yeas and nays of the Texas Legislature, which meets every other year.

That gathering is too often, if you ask some, but the state constitution being what it is, that’s how they do it.

So, while sitting recently enjoying a cocktail at the allotted time of the day, I was asked by my friend Martinez if I’d ever owned a pair of brass knuckles, which, along with tomahawks, nightclubs and mace, had been given a new status of “legal” by the Legislature.

I told him that I had not, that those seemed to be the tools of another element of humankind, where I wasn’t welcome. I also relayed a story I’d recently read about an incident that took place in the Lufkin jail in the early 1900s.

As the guard tried to rouse three inmates sharing a cell for breakfast, only one of the occupants appeared.

His name, according to the account, was Wilson, who, when asked, didn’t know where the other two were.

When the jailer made a personal inspection of the cell, he found one of the men, Traweek, dead, his head crushed into a pulp and lying “bathed in his own blood.”

Another man, Chandler, was found in a similar state.

When asked about what had happened, Wilson said that they had had a “little row” during the night and that he had “fixed them with that heavy iron slop bucket in the corner.”

Chandler, by the way, was in there after a conviction of carrying brass knuckles, now legal 120 years or so too late for him.

“So, if the time comes, I’d prefer an iron slop bucket in the corner – an empty one — as a force equalizer than brass knuckles,” I said.

This is why Dear Abby, even in her current state and reincarnation, has no fear of competition in the genre of advice, at least not from this writer or some others I saw on Sunday.

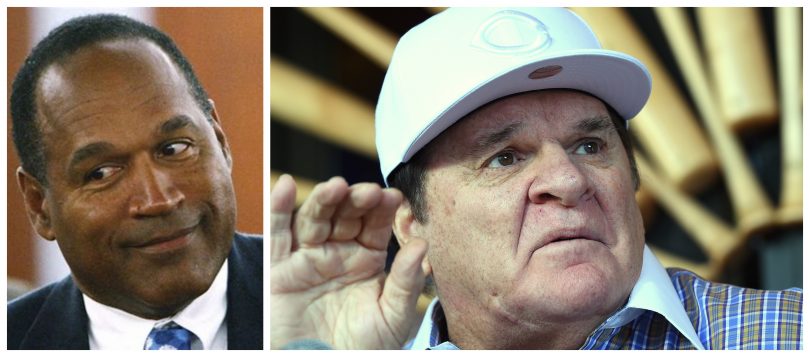

O.J. was on Twitter giving his seven habits of highly effective killers.

The Juice, smiling and amicable in a golf cart while in full remake mode after a stint in the hole and a near unanimous belief he’s a double murderer, was actually giving fantasy football advice to his now more than 792,000 and counting followers. Don’t be, um, afraid to take a running back unless Patrick Mahomes is available, he suggested.

Nowhere to be found on his draft board was Kato Kaelin.

He didn’t say, but O.J. is presumably very much a tomahawk guy. My advice is to steer clear. Do you think the almost-72-year-old O.J. would like a do-over of that day in June 1994?

There was yet another guy out there giving advice.

Pete Rose is taking a break from the autograph circuit to peddle his new book, Play Hungry: The Making of a Baseball Player.

Pete is making the rounds trying to sell books. There are always diversions into other topics.

Recently, he advised – no, make that insisted — during an interview session on the radio in the northeast that if given the option, there is only one guy in the modern era you’d start a baseball team with.

Alex Rodriguez, even with all the baggage. Well, Pete didn’t even acknowledge all the baggage. Takes baggage to ignore baggage.

Pete gave a preamble, too, assuring his inquisitors that the integrity of his belief lay in the fact that, “I don’t think there’s anybody in the country who knows baseball better than me.”

He wasn’t tooting his own horn, he said with that Rosean-Rocky inflection, “I’m just telling you the truth.”

And, while they were on the topic, sort of, why did Derek Jeter want that job in Miami, Pete mused?

“He’s got to have $250 [million] in the bank. You need more money?

“I don’t think I could leave this studio today and run the Reds tomorrow,” a deferential Pete said. “I think Jeter is learning that now. Running a baseball team is difficult. It takes a different mentality to run a baseball team. It’s not like playing the game.”

Pete has already more than suggested that he would like to have the late-1980s back.

Namely, mace the advice of bookies. More likely, not left the paper trails Bart Giamatti’s people used to corner him 30 years ago in 1989.

In receiving baseball’s ultimate sanction, Giamatti gave Pete some advice going forward. Giamatti had an open mind to reinstatement, he said, but “the burden is entirely on Mr. Rose to reconfigure his life in a way he deems appropriate.

“Let no one think that it did not hurt baseball, but this is a resilient institution that will go forward, and in the final analysis the public’s confidence will be strengthened because it should be clear that no matter who you are or what you’ve accomplished, grave accusations of this type will be pursued vigorously.

“Let there be no doubt about our vigilance — and patience — in protecting the game from blemish or disgrace.”

The very next week, Giamatti was dead, felled by a heart attack at age 51. He never handled a Rose reinstatement hearing. His successors have denied them all.

Speaking of baseball’s most notorious, June 24 was the anniversary of the banishment of umpire Dick Higham in 1882.

Higham is to this day the only umpire to be banned from baseball.

His sin was presumably an association with gamblers and fixing games, though a full accounting of the allegations and records of hearings dealing with them are insufficient for history to make a clear judgment.

One accounting tells the story of Detroit Wolverines owner William G. Thompson being suspicious about Higham following several calls made against his team. In those days, umpires were assigned to teams. Thompson, the story goes, hired a private detective, who was said to have uncovered letters between the umpire and a well-heeled gambler.

If the gambler received a telegram from Higham saying, “Buy all the lumber you can,” the gambler was to bet on Detroit. If the gambler didn’t receive a telegram, he was to bet on the opponent.

Higham never confessed to any wrongdoing and denied the accusations. And, according to the Society for American Baseball Research, Higham’s activities were never “the subject of any investigations by any private detective, nor was he ever confronted by the findings of any private detective; he did not draw any suspicions of the owner of the Detroit team for their losing out on close calls or having close games go against them.”

You never know. Perhaps they were making nightsticks with all that “lumber.”

Hard to tell. Few among us are all that concerned about it today.

Me and Dustin Hoffman’s Rain Man, perhaps.

Same goes for poor Bill Kunkel, who was the subject of baseball belittlement after of a blown call in Oakland 40 years ago on Monday.

With the Rangers up 3-2, Oscar Gamble and Billy Sample led off the fourth with consecutive base hits. Johnny Grubb, the next hitter, tried to advance the runners with a sacrifice bunt, but he didn’t get it down, instead popping it up to the third-base side. Oakland third baseman Wayne Gross charged in to try to catch it, but short-hopped the ball.

Gross wheeled and fired the ball to second, trying to force Sample, but his throw was wild and sailed into center field.

Third-base coach Frank Lucchesi sent Gamble and Sample both home.

What few, if any, except Tony Armas, knew was that in umpire Bill Kunkel’s judgment, Gross caught Grubb’s sacrifice attempt.

That meant not only one out, but, with former baserunners Gamble and Sample in the dugout, three.

Armas, the center fielder, retrieved Gross’ wild throw and flipped it to Dave Chalk, who stepped on second for out two. Chalk apparently didn’t realize he had another double up – Sample at first. Armas ran into the infield, took the ball from Chalk and ran to step on first, giving him an assist and a putout on the triple play.

Rangers manager Pat Corrales then did his best Earl Weaver impersonation. Hell hath no fury like a manager who just watched a bases loaded-and-no-outs situation turn into no runs and three outs.

“I couldn’t believe it,” said Corrales, who managed to avoid the ejection finger. Kunkel “knew he was wrong, and he knew I knew he was wrong.”

Said Kunkel: “In my judgment, he caught the ball. I pointed fair and yelled, ‘It’s a catch.’ I would have bet my paycheck at the time that I had made the right call.”

That would have been bad advice. Replays showed conclusively what everybody, but one guy, saw.

No one doubted Kunkel’s motives. He was a fine man of strong character. He just blew a call that day in Oakland.

No need for brass knuckles.