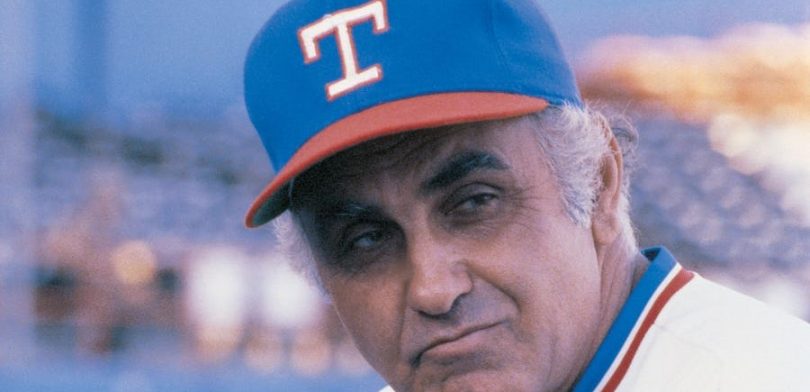

Frank Lucchesi, above all else, was a showman. Being a baseball manager gave him ample opportunity to display his God-given theatrical talents because it put him on a stage in front of thousands of people.

Frank wasn’t one to let those opportunities slip away.

There was, for instance, the time when he was managing in the minor leagues and became so incensed over being thrown out of a game that he sprinted into center field and climbed the 20-foot light pole there. The game was stopped for 20 minutes or so before umpires, players and club officials, using threats, pleas and promises, could finally cajole him into climbing down.

Frank would say later that it wasn’t until he got to the top of the pole and looked down that he remembered that he was terrified of heights. That, he said, is why he stayed up there so long; he was afraid to climb down.

I’ve often wondered what else Frank saw from up there. Must have been a pretty good seat for a ballgame. Today, though, Frank has an even better view, back on the front step of the dugout for Heaven’s home team. I can see him now, touching the bill of his cap, tugging on his ear, swiping his cheek, slapping his arm, giving signals to the third base coach to relay to the batter at the plate.

Back in a baseball uniform, standing on the top step, that’s Frank in all his glory. Except glory looks a little different to him today.

Frank passed away quietly at home in his bed Sunday morning. His wife Cathy, his biggest fan for 68 years, daughters Karen and Fran, and son Bryan, lay around him on the bed. That’s another visual that I can only imagine, but one that will also stick with me for a long, long time.

Frank, 92, had been in ill health for years. Four years ago, doctors told him that he had three months to live. Frank took it just as he did when an umpire booted him out of a game, something that happened 61 times during Lucchesi’s career managing in Philadelphia, Texas, Cleveland and Chicago. He knew he would eventually have to go, but he would do it on his own terms, kicking and screaming every inch of the way.

Frank’s volatile Italian blood rose at the challenge and he fought on for 48 more months, on a feeding tube that entire time. He had been under hospice care for the last year.

His daughter Karen told me they understood the time was growing near when he lost the strength to walk a few weeks ago. The family helped carry him from the bedroom to the bathroom and back again. By that time, he had withered away to a mere shadow of the robust and energetic man he had always been. All 5-foot-7 inches of him.

Frank was an old-school baseball man from the get-go. Today’s newfangled baseball analytics, all the talk about spin rate for pitchers and exit velocity for hitters, would have meant little or nothing to him. He knew baseball players when he saw them. He didn’t need a radar gun to know if a pitcher could pitch. He didn’t need to know what percentage of the time a hitter put the barrel of the bat on the ball. He could see that for himself, thank you just the same.

It is a pity, really, that my memories of Frank are marred by two very regrettable – and certainly avoidable – incidents that came to define his time in Texas. He deserved better than that.

The first, and most horrific, was when Rangers infielder Lenny Randle, who was trained in karate, assaulted Frank on the field before a spring training game with the Minnesota Twins in Orlando, Fla., in 1977. Randle was upset that Lucchesi had named rookie Bump Wills his starting second baseman. He walked up to Lucchesi, who had just arrived at the ballpark and was still in street clothes, and launched a cowardly, premeditated attack. Sucker-punched, Frank went down without ever having a chance to defend himself. Randle continued throwing punches while his manager lie senseless on the ground before finally being pulled away.

When Rangers outfielder Ken Henderson heard what had happened, he had to be held back from going after Randle, who had picked up a bat and strolled out to center field. Other players were just as incensed. General manager Eddie Robinson finally had to walk out to Randle – hoping that Lenny wouldn’t decide to use the bat on him – and talk him into coming off the field, where he would face an immediate suspension. Randle’s career in Texas was over from the moment he threw the first punch. He was soon traded to the New York Mets and never wore a Rangers uniform again.

Frank was hospitalized with a fractured cheekbone, broken ribs and other assorted injuries. It would be weeks before he was able to resume managing.

Frank sued Randle for $200,000. Even that grew ugly when Randle played the race card. Frank Lucchesi was never, by any stretch, a racist, but his reputation had been unfairly tainted. It was as if Randle had launched yet another scurrilous attack. The eventual settlement was just enough to cover Frank’s medical expenses.

The second regrettable incident came when Frank was fired by then-owner Brad Corbett less than halfway through that same season. The Rangers weren’t playing particularly well, but they were sitting exactly at .500, 31-31 for the year, only a few games out of the West Division lead. The firing caught Frank completely by surprise. Word that Eddie Stanky would be the Rangers new manager – he would last just one game, but that’s another story – leaked out just before the team left for a long road trip and things got messy.

Frank dangled in limbo for a few days in Minneapolis before the axe officially fell. Frank was miserable and the tears flowed that afternoon at old Metropolitan Stadium. There was no manager’s office in the visiting clubhouse, so a heartbroken Frank huddled in an equipment room with reporters as he agonized over how his teenage son Bryan would take the news.

Frank loved being a major-league manager. It was fun to watch him walk into the Banyan Room of the Surf Rider hotel, where the Rangers headquartered during spring training in Pompano Beach, Fla., carrying a stack of 8-by-10s of himself in his Rangers uniform. He would introduce himself to whatever fans might be there and autograph a photo for anyone who asked.

Frank always had a streak of Vaudeville in him and enjoyed letting it out to sing and dance. Once after being ejected during a game, he yanked second base out of the ground and threw it into the stands. He made an absolute art form out of kicking dirt over home plate or, his preferred target, an umpire’s shoes.

A TV crew wired him with a microphone for a nationally televised game in Boston one afternoon. They wanted the TV audience to be able to listen in as he managed the game. The Rangers, however, could muster little or no offense. Frustrated at being unable to display his managerial skills to full effect, Frank finally called for a rare Rangers’ base runner to steal second. Problem was, the runner was Rangers’ backup catcher Bill Fahey, perhaps the slowest player on the team. Predictably, he was thrown out. Naturally, Frank was glum the rest of the day.

I was incredibly fortunate that Frank was the manager when I started covering baseball in the mid-1970s. He was following Billy Martin, a far more temperamental skipper than Frank ever thought about being, and he was more than happy to show a new baseball beat man the ropes. He was kind, gentle and fatherly, setting the foundation for a close relationship that would last almost half a century.

Our only cross words in all that time provided Frank with one of those dramatic opportunities he loved so much. Back in those days the Rangers beat writers from the three papers – the Star-Telegram, the Morning News and the Times Herald – rotated as official scorers for games.

I was the official scorer one day when I caught just the tail end of a play and called an error on a ball that outfielder Tom Grieve had smoked to the opposing second baseman. The Rangers’ dugout erupted with players hopping out to glare at the press box. Frank rushed out, waving a white towel in my direction.

Moments later the press box phone rang. It was Lucchesi, calling from the dugout to say that that was the worst call he’d ever seen in all his days in baseball. With colleagues all over the press box screaming at me not to change the call, I quickly conferred with Rangers’ PR man Burt Hawkins and resolved that I had blown it. I immediately changed the error to a hit. The right thing is the right thing.

After the game, when reporters had gathered in Frank’s clubhouse office for postgame interviews, I made a point of telling him that he didn’t need to call the press box to yell at me, since he knew I’d be coming straight to him after the game anyway.

Frank exploded like Mount Vesuvius. No need to detail everything that was said, but rest assured, it was all delivered at a painful decibel level. As the brunt of Frank’s rage, I was learning firsthand how an offending umpire must feel. I was just happy there was no dirt for him to kick all over my shoes.

I eventually gave up trying to reason with him and left. A few minutes later Frank walked out and beckoned third base coach Connie Ryan over. A colleague overheard him whisper, “Could you hear all that out here?”

I had been made the straight man for one of Frank’s theatrical productions, one the manager hoped would build his image in the eyes of his players. Frank was making sure that his troops had been able to hear him sticking up for them.

I shrugged it off. It had all started with me blowing the call, after all. It had no effect whatsoever on our relationship going forward. We both knew that each of us had jobs to do and we would do them to the best of our abilities.

We only grew closer over the years, though we didn’t see each other often. When we did, there were hugs and smiles and it felt like old times again.

I found myself wistfully wishing Sunday that I’d asked Frank for one of those autographed 8-by-10 photos myself.

(Photo: Texas Rangers)