Along with the unpunctual summer heat, July of 2019 brought with it the deaths of two notable, yet quite different, public servants and sports fanatics, whom no one should ever forget.

This week, a giant in the community of law, retired Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens, the gentleman and scholar, fell ill in Florida and died on Tuesday at age 99. His prestigious place on the nation’s highest court identified him to the masses, though he likely saw himself very differently.

Stevens forever was the 9-year-old boy going to his first Chicago Cubs game at Wrigley Field, the start of a love affair that never abated, even through all those ghastly baseball seasons that branded fans with both character and lasting scars. In the end, he lived long enough to witness the Cubs finally win a World Series in 2016.

From his seat at Wrigley Field as a 12-year-old, he watched Babe Ruth, responding to the Cubs bench’s incessant hazing from the dugout, point his bat to center field in Game 3 of the World Series and then on the next pitch hit a home run to that exact spot.

It was Ruth’s so-called “called shot” that has stirred so much controversy, even for Stevens, who once had a law clerk investigate where the ball landed. At a convention, an attorney approached Stevens to challenge him on his recollection of where the ball landed.

Stevens, concerned his aging memory might have caused him to misstate facts, was right. The called shot was to center field. Ruth hit two home runs that day. The other was to left.

Stevens, who spent four decades as an associate justice, will lie in repose at the Supreme Court before his family takes him to his final resting place at Arlington National Cemetery.

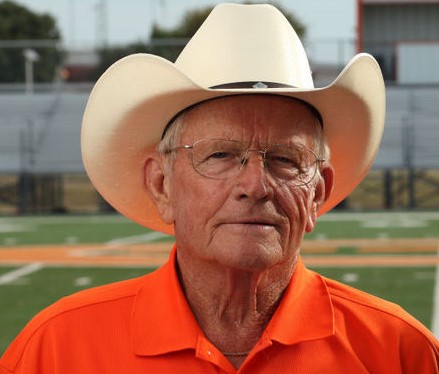

In another place and time — about two weeks ago, to be exact – stood Texas high school coaching icon G.A. Moore at the foot of St. Thomas Aquinas Catholic Church in Pilot Point.

Pilot Point, roughly an hour north of both Dallas and Fort Worth, is Moore’s hometown, the place where he achieved holiness by winning back-to-back state championships in 1980 and ’81 during a nine-year stretch in which he won 106 games and lost just nine.

On this particular day in July, Moore was tasked with eulogizing one who had not only seen all of that but was a big part of it.

Geraldine Curry was born Geraldine Blumberg and raised in Pilot Point and never left. She died there, on July 7, at age 76.

Three times Geraldine survived cancer.

She and her husband Henry, with only daughters on the roster, never had a football player at Pilot Point, but Geraldine was the Bearcats’ biggest supporter on Friday nights.

“She was just an outstanding supporter,” Moore said. “She supported us because we were Pilot Point … Orange and Black. It didn’t make any difference who they were playing. She loved Pilot point.”

Pilot Point was the prototype Texas high school football town. When the workday ended on Friday, it was off to the game to watch the boys play for the pride of Smallville, from cotton to cows to the smell of a cattle drive or an oil derrick in the setting. Everything stopped for three hours, the game the unifying force that brought, in some cases, the entire town together.

In some places, it’s still that way, of course.

The game’s character and legend are made up as much by the fans as the players.

Geraldine was part of a group of boosters who decorated the town, decorated the lockers of the players and the school hallways, and marched up and down the hallways on Friday offering encouragement.

“We had a terrific group of ladies here,” Moore said. “Anything you could think of they did. She was a big part of that.”

There is a story that she was so involved with the football team that she sat in on coaches’ film sessions. Not with Moore, however. Moore said that it’s possible she did that with his successor, Jerry Jones. (Not that Jerry Jones.)

That story might have been confused with a Thursday night tradition in Pilot Point.

Players and their parents would gather for a meeting. Some film would be shown there, too.

Geraldine was there every Thursday with her time-honored banana pudding.

“She had to bring a bunch,” Moore said. “The players loved it. She was famous for that.”

Moore went back to Celina in 1988 and won five more state championships. If you count the state championship Celina shared with Big Sandy in 1974, Moore won eight state titles. In that 1974 game, Celina shocked No. 1 Big Sandy, featuring Lovie Smith, by managing a 0-0 tie.

Geraldine never left, her devotion to Pilot Point an integral part of her being. Moore said even up until last season, she was at the games, sitting in her wheelchair on the field.

“I don’t guess she ever missed a football game. And she never missed a softball game,” Moore said. “She fought it all the way up to the end. She was typical of what it was like to be a football fan. She didn’t care whether it was my kid or someone else’s kid, if they were in the orange and black of Pilot Point, she was for them.

“She loved it.”

After all, Orange and Black forever meant just that.