In the excellent 2015 movie Concussion, the role of Roger Goodell, sovereign lord of the NFL, is played by comedic actor Luke Wilson.

I guess Curly, Larry and Moe weren’t available.

Wilson’s portrayal is not one of his best, but the script admittedly didn’t give him much to work with. While NFL players are dying in the movie and battling with CTE-induced dementia, the Goodell character seems to blend into the beige hotel carpeting, so much so that I don’t recall Wilson uttering a single line.

Before the film’s release, the New York Times reported that Sony executives had been urged in private emails to amend parts of the script that the NFL found “unflattering.” The wardrobe people didn’t even bother to color Wilson’s hair in Goodell’s signature ginger.

Maybe I just missed it, but Concussion is not available on Netflix. That’s not to imply that the NFL commissioner’s office can unduly influence our on-demand viewing choices, but I’m reminded of perhaps the movie’s most memorable line.

In it, county medical examiner Dr. Cyril Wecht, played by Albert Brooks, warns the story’s protagonist, portrayed by Will Smith, of the formidable adversary he is up against:

“Bennet Omalu is going to war with a corporation that has 20 million people on a weekly basis craving their product, the same way they crave food.

“The NFL owns a day of the week. The same day the church used to own. Now it’s theirs.”

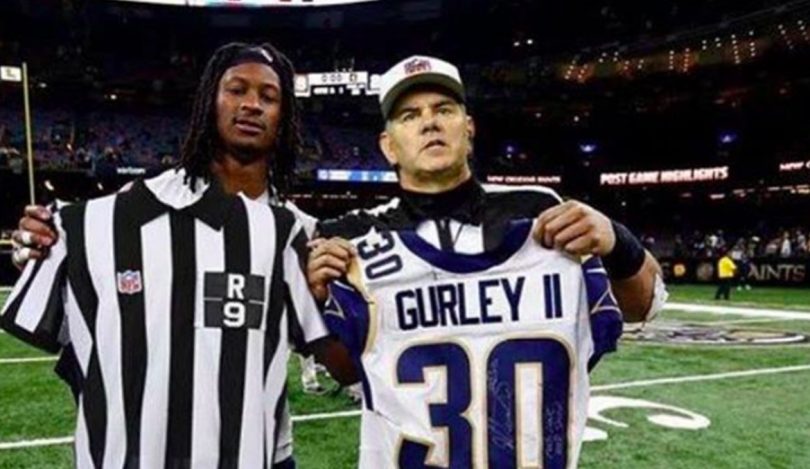

It was a Hail Mary’s throw, at best, therefore, for those two fans in New Orleans to hope that their lawsuit would muster so much as an acknowledgement from the great and powerful Goodell. The plaintiffs, Saints ticket holders Tony Badeaux and Candis Lambert, are seeking (pick one) a replay, a do-over of the final two minutes, a public explanation from Goodell – or anything, really — that will assuage their anguish over the blown call at the end of the NFC Championship Game.

We’ve already done that, somebody from 345 Park Avenue sniffed. Senior vice-president of officiating Al Riveron admitted the non-call was incorrect in his phone call after the game to New Orleans coach Sean Payton.

Goodell himself has not commented before today, a silence that has not gone unnoticed.

As veteran Saints tight end Benjamin Watson wrote on social media, Goodell’s public silence on the non-call “is unbecoming of the position you hold, detrimental to the integrity of the game and disrespectful and dismissive of football fans everywhere.”

The legal case is a nuisance as much as anything. I realize that. But the plaintiffs were right to attempt to parade Goodell, the self-proclaimed protector of the league shield, in front of the dismayed fans of one of his franchises.

This isn’t whining about a missed call. It’s an integrity issue. The entire country saw the egregious error. Goodell should have publicly summoned the entire officiating crew to the NFL office. An announced suspension of one or more of them would have been roundly applauded.

Whining? Oh, please. If the same botched call – under the same Super Bowl-on-the-line circumstances — had happened to the Cowboys or, say, Broncos, fans and media would be screaming just as loudly.

We certainly wouldn’t have heard the same weak response from Cowboys executive vice-president Stephen Jones, a member of the league’s competition committee, who said, “At the end of the day, it’s the official’s call, and you live with that.”

When asked about the possibility of expanding the NFL replay system to include pass interference calls, Jones replied, “Certainly you don’t want to officiate from replay. I don’t think, at the end of the day, it’s good for the game.”

But that is laughable. At the end of the day, the only consideration should be getting the call right.

If I may, let me offer Son of Jones and all the competition committeemen a handful of suggestions:

1, Expand the replay rules to allow challenges for pass interference. Coaches are still going to have only a set number of challenges. If the concern is lengthening the time of games – the non-call in New Orleans would have taken, what, 30 seconds? – the rules can be tweaked to remove those ridiculous “icing the kicker” timeouts at the end of halves. Or stop allowing coaches to challenge spots of the football. It’s taking 3-4 minutes for replays to adjudicate 4-5 inches.

Our Canadian brethren in the CFL have allowed their coaches to challenge pass interference calls since 2014, and anarchy has yet to break out. What has evolved, it seems, is that coaches are saving their challenges for those critical pass interference moments – 42 of the 71 challenged calls this past season. Of those 42, 19 were overturned (48 percent).

As CFL spokesperson Lucas Barrett told Reuters, “The CFL introduced video review to fix egregious and indisputable calls that could affect the outcome of a game. To ensure that was the case, defensive pass interference was added to challengeable plays for the beginning of the 2014 season and played a critical role in the 103rd Grey Cup in Winnipeg.”

2, Consider radically expanding the number of officials that work each game.

I’ve never understood why football thinks it can be officiated correctly when you have 50- or 60-year-old officials chasing superbly conditioned 20- and 30-year-old athletes up and down a field that measures an expansive 360 by 160 feet.

On every play, too.

Think about it. Officials don’t get to take a series off while the defense is on the field. The same seven guys have to run and monitor a playing surface of 57,600 square feet.

If you expand a game crew by, say, four officials, it would allow time for referee substitutions. Or you could employ separate crews at opposite ends for the three most critical pass play assignments – field judge, back judge and side judge.

None of this, of course, is going to quell the uproar among Saints fans. The lawsuits, billboards, governor’s pleas and statements from the Senate floor all served their intended purpose and underscored the community’s outrage.

But by responding with silence, Goodell only kept the officiating controversy on the front burner.

He finally will talk Wednesday at the Super Bowl, when he holds his annual state-of-the-league news conference. Certainly, he will be asked about the NFC title game gaffe.

With 10 days having passed since the blown call, Goodell is likely to deliver a measured response that offers a consoling shoulder for Saints fans. Something along the lines of, “We think we have the best-officiated game on the planet. You never want to remove the human element from the games. The officials made a human error, and I feel bad for the Saints. We will review our officiating rules to make sure this doesn’t happen again.”

Pretty lame, but we were never going to get side judge Gary Cavaletto’s head on a stick.

I’ve tried to imagine an equivalent officiating misdeed, given the circumstances. The Dez Bryant catch in Green Bay comes to mind, but the controversy was over a rule interpretation, not a blatant instance of referee incompetency.

Try to imagine, instead, that it’s the seventh game of the American League Championship Series, and the score is tied in the bottom of the ninth at Yankee Stadium. Aaron Judge hits a home run into the center field seats. “Foul ball!” the umpire says. The game continues, and the Red Sox score a run in the top of the 10th to win the game and the series.

Would the commissioner of baseball sit idly by and say nothing for 10 days? Of course he wouldn’t. No commissioner with character and a concern for integrity would.

But this is the NFL. Move over, churches.